What It Takes To Have a Dialogue

In our society today, people are having trouble communicating. When discussions take place, they aren’t listening to each other or taking the time to formulate a thoughtful response. Nor are they conducting the conversation in an open-minded, respectful way. As a result, the discussions aren’t leading to learning or growth. Without the capacity for productive discussion, people are denied the opportunity to participate in the process of dialogue, wherein new ideas and important personal truths are generated.

So then, let’s begin: What is dialogue really, and how can we learn to do it in a helpful way?

What is Dialogue?

Most people think of dialogue as the act of two people talking to each other. While that may be technically true, the word has a more nuanced definition. It conjures the image of working something out, going on a kind of journey towards new ideas and a fuller understanding of a subject. More than just a single instance of conversation, it’s an iterative process of taking in someone else’s ideas and passing them through the lenses of logic and emotion; formulating a response based on thinking, processing, and consultation; and arriving at a conclusion that is new and often surprising.

A healthy dialogue doesn’t end with you feeling the same way you did when you came in. It always involves the generation of new ideas. At the very least, you should walk away understanding your current position in a new way.

Over time, acts of dialogue reshape who we are. There is no more satisfying learning than the kind that occurs from the slow recognition of genuine truths within yourself. Once these truths are realized, they become intellectual guideposts that make up a kind of mental map for you to live by.

What Does A Healthy Dialogue Look Like?

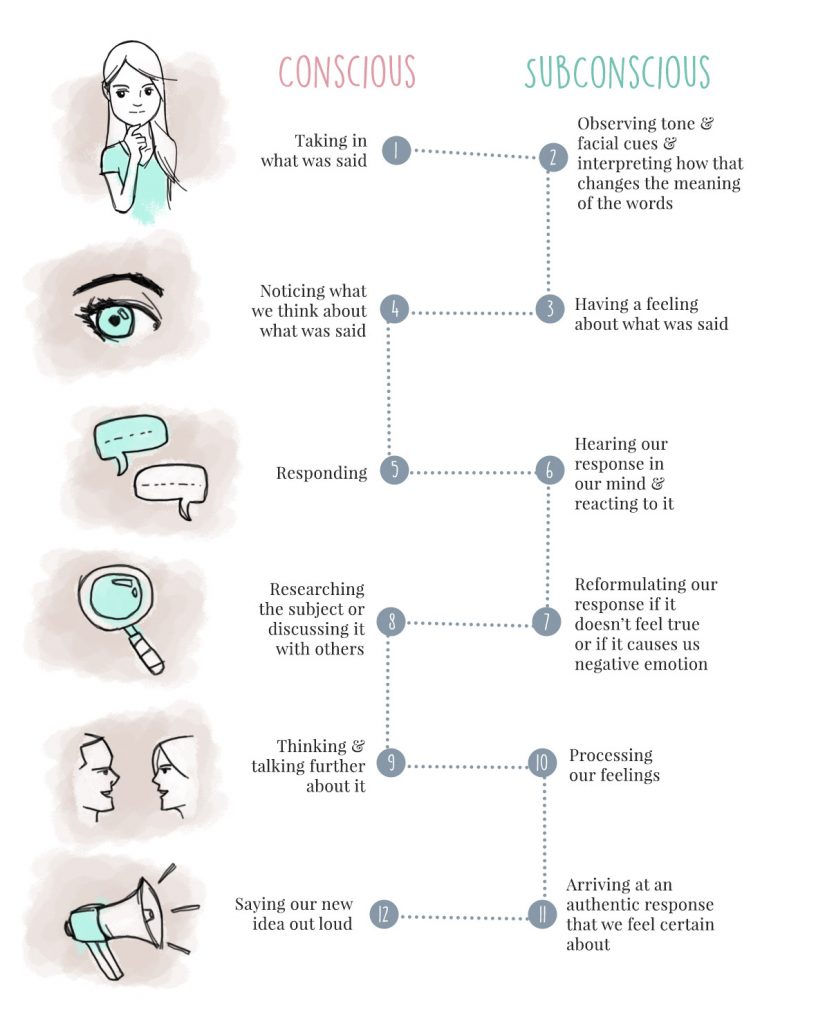

Below, I’ve attempted to illustrate what a healthy dialogue looks like from one participant’s point of view. There is no need to study it; the main point is simply that a lot takes place both consciously and subconsciously during a dialogue.

People tend to do all right in the early part of the dialogue, particularly on the conscious side. Where they fail is on the subconscious side, specifically in recognizing their emotional reaction to someone’s perspective (step 3), and then at the final step, when attempting to articulate a response that’s truly their own.

I’ll go into both of these problems separately, as they’re the two major issues that prevent people from communicating effectively.

Recognizing Our Subconscious Emotional Reaction

The first problem people have in dialogue is being able to take in the other person’s point of view and understand how much of their reaction to it is emotion and ideology. Most of us are good enough at listening to another perspective and even stating a reasoned reply, but what we don’t see is that the moment we take in a statement, it is dipped in a murky subconscious solution and presented back to the other person full of emotion.

Separating objective statements from feelings is an insurmountable problem for almost everyone because how we feel is much more powerful than what we think. For instance, imagine an important politician makes the statement “We’ve sent jets into Guatemala.” Depending on who you are, that statement can be interpreted as either “That warmonger sent jets into Guatemala” or “Our hero sent jets into Guatemala.” Even though the objective part of the statement is simply that the politician sent the jets into Guatemala, suddenly the matter is drenched in emotion.

There’s nothing wrong with having an emotional reaction to a statement. But in an ideal world, we’re able to recognize that it’s happening and understand that others will have different perspectives and emotional responses that are equally valid. The goal is not to be right, but to understand what’s occurring so you can determine a healthy next step in the dialogue.

In a political conversation like the example I gave, neither you nor the people you’re speaking with have much control over the situation, so a healthy next step would be engaging with your feelings on the matter, recognizing the ideologies and original causes behind those feelings, and trying to understand where others are coming from. Doing these things will make you feel better and prepare you for a productive discussion with the other person, which is indeed a healthy next step.

The alternative would be not engaging with your feelings on the matter and simply remaining angry that others feel differently from you. This anger may devolve into helplessness and depression: “How can people think this way? What is wrong with the world?” Obviously, this isn’t a healthy next step.

It takes a lot of practice and discipline to be able to think through what’s happening inside us during an emotional situation. And it isn’t always possible. But learning to do so develops a mental tool that can resolve a lot of confusion and strife, and allows valuable dialogues to take place.

Finding Our Authentic Response

The other place where people fail at having a healthy dialogue is at the very end: stating a new, authentically-felt position on the subject. It’s difficult enough to do everything that comes before — understanding your emotional reaction to what was said, thinking the subject through, consulting other sources, and noticing what your subconscious processing has brought forth — that the task of finding the words to describe your new belief can feel like a tall order.

Doing so is a matter of active thinking. Whereas passive thinking involves calling up phrases you’ve heard frequently or recently without deciding whether they’re really right for the occasion, active thinking is the opposite: coming up with the words you feel best fit the concept you’re expressing. Sometimes the right words are simple ones, even cliches, but you can always recognize active thinking in a person because their words sound a little more interesting due to their originality.

For example, if someone asked “What rights are all people entitled to?” it would be hard not to respond with a pastiche of phrases you learned in school and have been reinforced over the years such as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” “treated with dignity,” “equal under the law” “religious freedom,” and “freedom of speech.” However, this would be passive thinking because it involves recall as opposed to synthesizing concepts in a novel way.

One answer that involves active thinking would be Yuval Noah Harrari’s in his book Sapiens: “Humans have no natural rights, just as spiders, hyenas and chimpanzees have no natural rights…There are no human rights, except in our collective imaginations.” However you feel about his answer, it is startlingly original and therefore a good springboard for dialogue.

When we express our thoughts and feelings in ways that feel genuine to us, they hold more weight in a dialogue and, most importantly, feel sturdier within us, forming more reliable guideposts for future wayfinding.

Where to Go From Here

I find the concept of dialogue very exciting. Not only is it satisfying to tame my primal reaction to someone else’s viewpoint, but learning how I actually feel about an issue produces an idea that wasn’t there before. It’s intriguing to think what new ideas I’ll find. I hope you stay and look around for a while, sign up to get updates when new content is published, or drop us a line to let us know what you think of the site.

This is a huge part of my living questions. As a student, an experimenter in connection and language. David Bohm’s book on Dialogue is outstanding. I love kind safe questions, via a Socratic approach that let our assumptions bubble up. I find the natural intimacy of dialogue no one leading just finding a way to get to the source without triggering a lot of defensiveness. What does it feel like to be you? I want to do this project and maybe get involved in your work.

Glenn

This website is a very neat idea and so necessary for the times we are living in today. Way to go guys/gals or whomever you are! I love it!