Culture and Its Impact On Us

As humans, we live and die by ideas. Whether it’s the idea that we’re free, that we belong to a particular group, or that we’re treated fairly, certain assumptions guide our behavior each day, hidden beneath our consciousness. Even though most of us believe our lives are shaped by free will interacting with external events, it’s actually our unconscious mind, made up of powerful-yet-invisible ideas, that most influences what happens to us.

For example, many of us go to a job each day. To do that, we need to maintain several assumptions that are so basic we barely ever look at them: that we’re a part of a larger entity, that we’ll be paid, that our work has value, and that that we’re progressing in our career. If any of these ideas were disturbed somehow — say we were to learn that our work was being discarded unused at the end of each day — we’d no longer want to go to our job. Without any external event, by way of a single idea, our lives would change.

Or, imagine one day you learn that you’re adopted and your real parents are royalty in a prominent European country. Just that idea alone, without any external event, would change your self-perception, and potentially your behavior, forever.

There are thousands of these “givens” in our lives. It’s empowering to bring them to the forefront of our minds so we can decide if we truly believe them, and whether they’re serving us. Doing so gives us greater mental freedom and conviction in what we believe.

Where Our Ideas Come From

As I illustrated above, our ideas drive our actions. We go to bed at 9pm because we believe we should show up on time to our appointment the next morning and would experience social disapproval if we didn’t. We have eggs for breakfast because we believe they’re an appropriate breakfast food, as opposed to beef stew, which isn’t. However, our ideas aren’t the only reasons we take actions. We also go to bed at 9pm because we feel tired and have eggs because we’re in the mood for them. But these conscious feelings occupy a smaller percentage of our decision-making than we think.

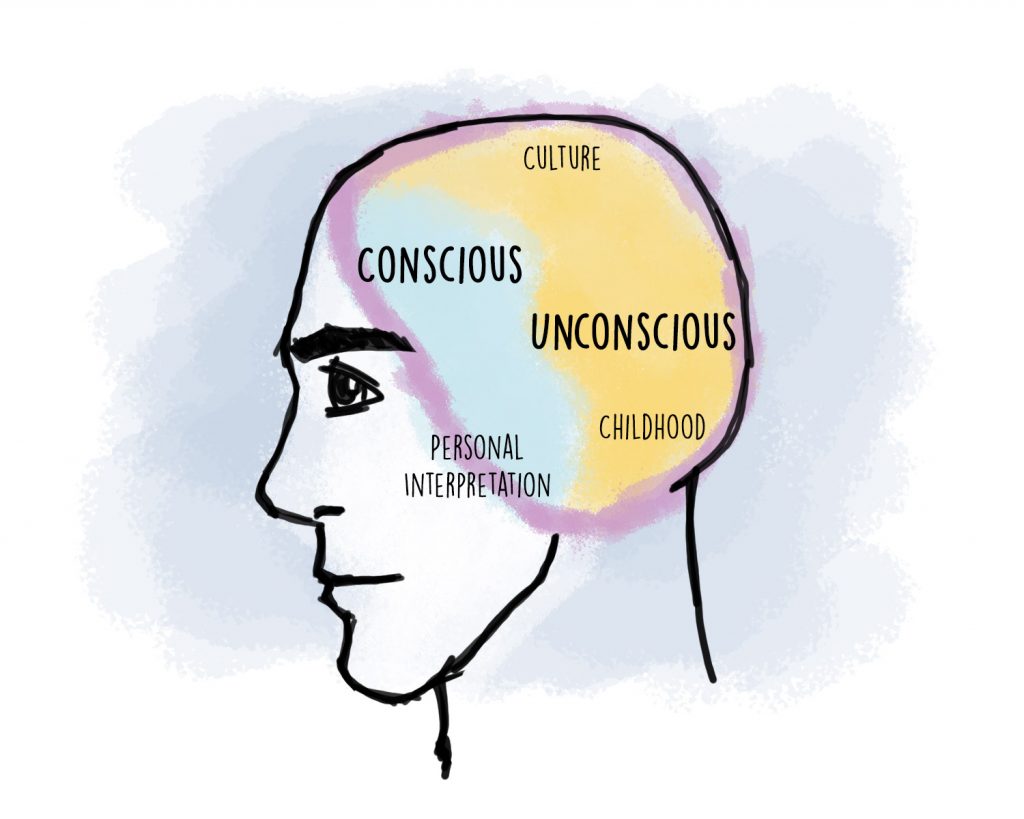

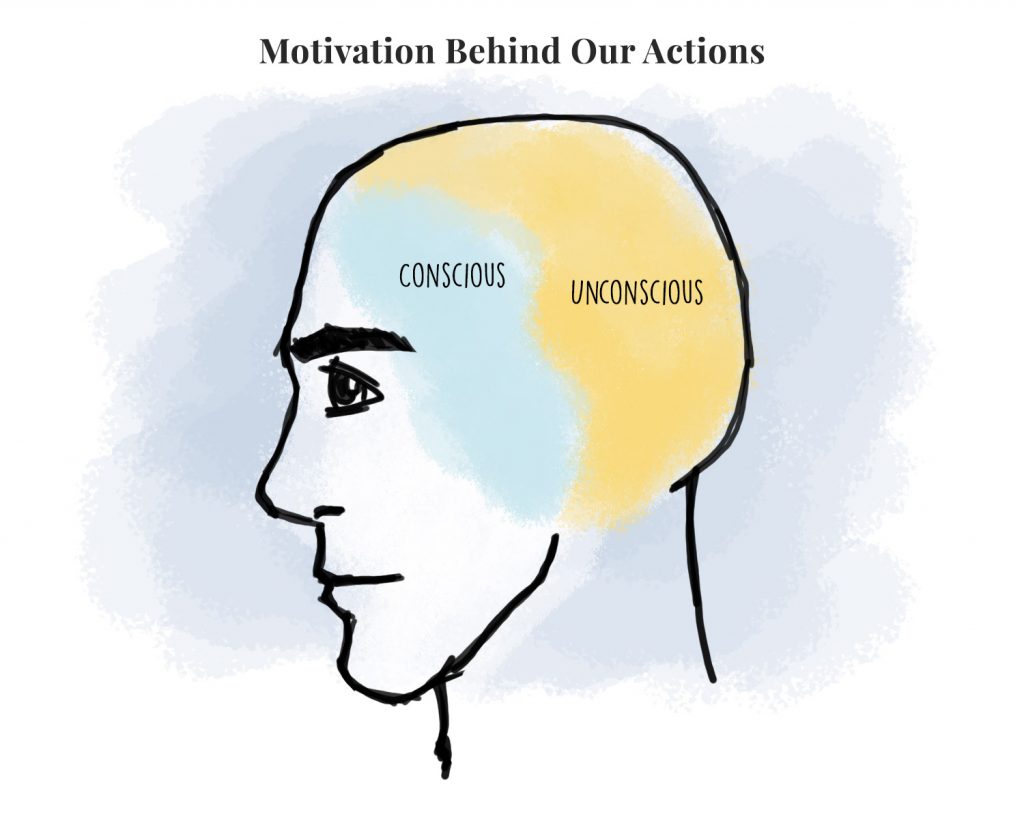

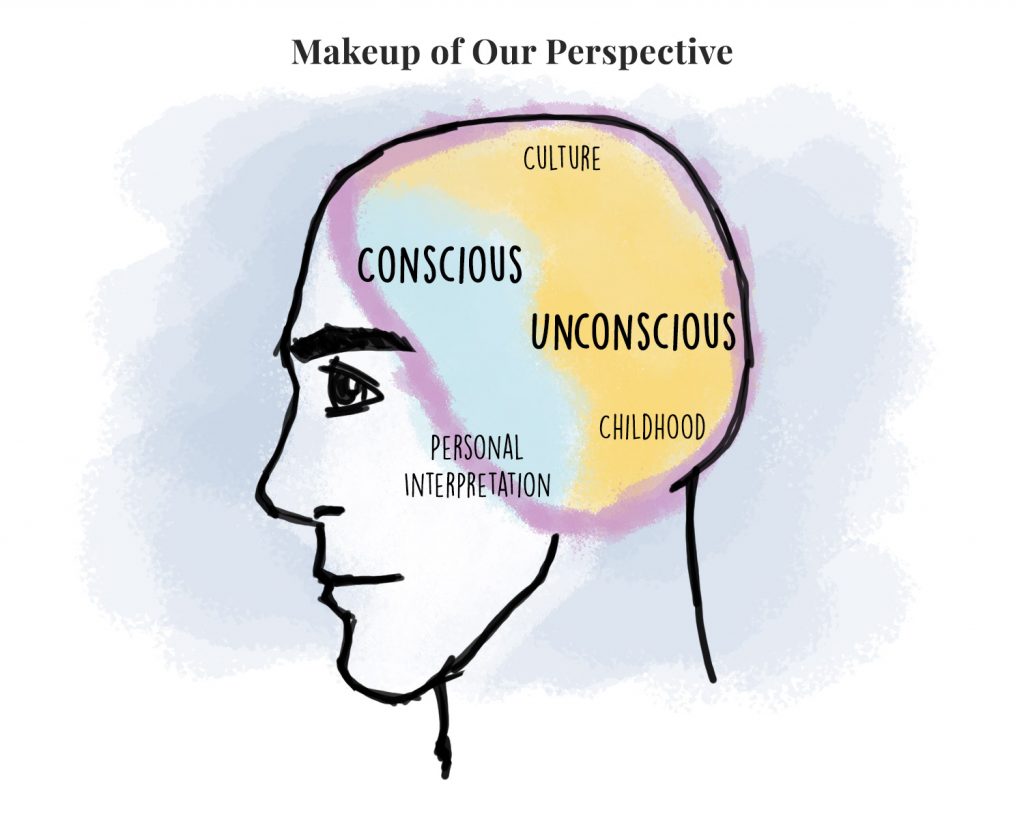

The motivation for each decision we make is, by my estimation, about 75% unconscious and 25% conscious. Going to the gym is a good example. In doing so, your conscious mind considers how you feel physically and how long it’s been since you last went. But the lion’s share of the decision consists of “givens” asserted by your unconscious mind such as, “I’m only acceptable at a certain weight,” “Looking fit is important to people valuing me,” and “I’m anxious and need something to make me feel better.” If those unconscious ideas didn’t exist, the conscious feelings alone wouldn’t be enough to motivate you to go.

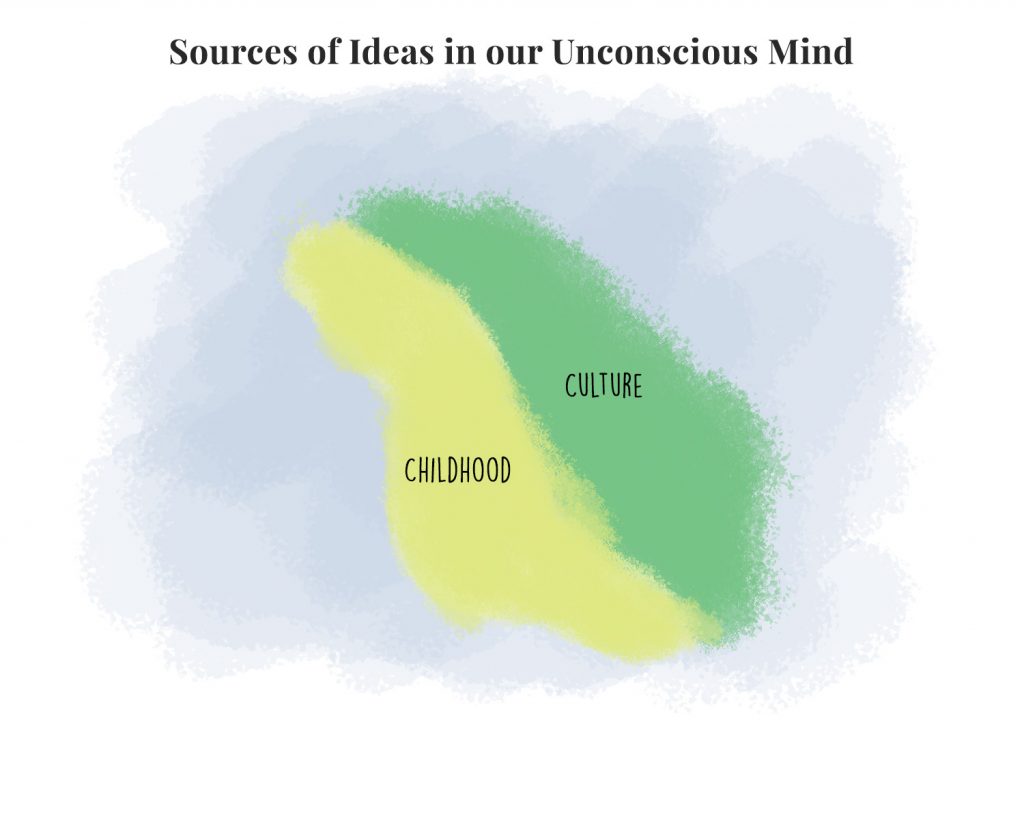

So if our unconscious ideas are so important, where do they come from? My belief is that roughly half of our unconscious ideas derive from our childhood, and half from our culture.

Our childhood produces the ideas we’d normally talk about in a therapist’s office — whether we’re worth loving, how secure we feel, what we do when we’re anxious. These ideas come from the broader trends of our childhood, such as how much time our parents spent with us, the degree to which they controlled our behavior, whether they felt proud or ashamed of us, and how they felt about themselves. Much of the realm of traditional psychology is based on childhood experiences like these. Less is based on the cultural side.

Culture, however, is an equally big influence on our decisions. To be clear, I don’t just think of culture in the popular sense of our traditions, holidays, food, music, and arts. I define it more broadly to mean all the things we consider “normal”: our beliefs, actions, and overall way of being. In its purest sense, culture encompasses the things we took in during our first weeks of life: the lull of our mom’s voice, the amount she communicated verbally versus nonverbally, the way she experienced food; as well as our father’s gait, the staccato of his speech, and the amount he interacted with us physically. We absorb these things as infants, shaping what we believe is “natural.” And all this occurs before we even have the aforementioned childhood experiences.

In my own personal development, I’ve spent more time considering childhood’s impact on my unconscious than culture’s impact. Doing so has served me well, as the ideas my younger self needed to survive are no longer relevant to my adult life, yet I was living by them as if they were absolute truths. Unearthing those ideas and observing how untrue, and even harmful, they were has been some of my most liberating work. However today, with those old childhood ideas mostly dealt with, I find myself noticing culture’s impact on me far more.

For instance, when it comes to who I like spending time with — friends, community members — I find myself drawn to people who remind me of the Long Island, Jewish culture in which I grew up. If I meet someone from that area, I immediately recognize the warmth, the dry sense of humor, the anxiety, the focus on academic achievement and material success, the unspoken preference for other Jews, and much more. When I compare this way of being that I’m so comfortable with to my current friendships, which are largely with people outside Long Island Jewish culture who are a bit less anxious and don’t care as much about traditional success, for instance, the results are interesting. While I can’t deny that the culture of my upbringing lives in my cells and will always be attractive to me, I feel more aligned with other ways of being and expect many of my future relationships to be with people outside the Long Island Jewish sphere.

To some, the idea of straying from your cultural sphere feels heretical, especially if left unexamined. Many people remain tightly inside the boundaries of where they feel they belong, sometimes uttering phrases like “I just like being around people who get me.” But if they could see the underlying reason for choosing their social niche, they could at least make a conscious choice about how much or how little to depart from it.

Culture’s Influence On Our Point of View

Culture shapes not just our decisions, but our opinions on everything from the temperature we like our bedroom at night to our political leanings. And although our strongest ideas come from our early culture, our existing community continues to shape our ideas.

When I was growing up in New York, there were recycling bins in some places, but putting items in them felt more like an act of altruism than an expected norm. Where I live today in Northern California, not only is recycling fully expected, but people spend time cleaning their recyclable waste to ensure it goes through the system properly. I spend more time thinking about trash in a week in California than I spent in the first 20 years of my life in New York.

Even though by now I’ve totally accepted the California way of recycling, I never thought about it until a few months ago. What happens if I recycle something with food on it — will someone’s future paper towels have traces of my smoothie in it? I probably could have found these answers easily, but up until recently, it hadn’t crossed my mind. The place where I live transmitted the normalcy of the behavior to me invisibly and I accepted it.

This is one way in which my point of view on what’s right has evolved based on culture. Of course, recycling is a fairly innocuous example, as it takes little effort and there isn’t much downside to it. But it raises an interesting question: What other things do we believe without question just because they’re part of our culture? Exploring this subject could reveal truths that haven’t seen the light of day in a long time. While we have an untold number of culturally-ingrained ideas, below are a few questions to stimulate thought or dialogue about less-examined subjects.

Easy Questions

- When is it okay to break a rule?

- To what degree are you trusting or distrustful of people you don’t know, and how has that served you in your life?

- How do you like to physically appear to others? How much effort do you put in to present yourself in a certain way?

Medium Questions

- What is your attitude towards correctness in conversation? How acceptable is it to say something without being sure you’re right?

- How much responsibility should you take for other people in your daily life? Should you be thinking about how your actions affect others all the time? If not, then in what situations?

- What’s your resting mental state? When you’re alone and not doing anything stimulating, where does your mind go?

Hard Questions

- What has changed about the way you perceive yourself now versus the way you saw yourself as a child?

- How much space do you deserve to take up in the world? When you feel like expressing something, how worthy of other people’s attention do you usually feel it is?

- Did your parents love you the way you wanted to be loved?

However you answered these questions, it’s interesting to think about whether you proactively decided on your opinion, or whether it just became your opinion at some point without your conscious consent.

The Search For A Unique Perspective

Discovering what is true to you on a deep level is one of the most freeing feelings a human can experience. Some seek personal truth in therapy, others in books, and others in psychedelics. Many people avoid it instead, choosing to feel better rather than to know better. These people will always be controlled by internal forces they haven’t chosen and likely aren’t serving them.

Even when we start to feel like we have a real sense of our values, principles, and beliefs, we can always look beneath them and find that the household, community, or society we grew up in influenced those beliefs. And yet, as much as our core beliefs are borrowed from the cultures we’ve been exposed to, we can still have originality in our words, style, and expression. This is the reason there can be hundreds of songs written about love that all mean something different to us. They may be variations on the same theme, but the magic, so to speak, is in the outer layer of personal interpretation.

Understanding where our perspectives come from moves us towards a challenging but enlightening reality: that all perspectives are equally valid. You may hold a certain social or spiritual principle dear, and likely, so do millions of people. At the same time, millions of other people don’t believe that principle at all. And neither group is wrong.

While this reality may seem like an impediment to communication and cooperation, it’s actually quite positive. A variety of perspectives gives us material to chafe against, contrast with, and borrow from. It stimulates dialogue. The more perspectives we’re able to see, respect, and engage with, the greater our capacity to develop our own beliefs and feel confidence in our movement through the world.

The hard part is accepting the subjectivity of your perspective.

Traveling to other places reminds me that most of what I think about myself and the world is determined by my environment (culture). Thanks for a great article! I look forward to listening to some dialogues 🙂